Heitor Gouvêa

A lightweight static security analysis tool for modern Perl Apps

Table of contents:

Summary

Through the use of static analysis tools, it is possible to identify many security issues quickly and in large and complex code base. But doing this efficiently is hard, as the complexity of using the tool can be high, there can also be many false positives and if that happens, the user experience will be bad and probably the use of a SAST in your development cycle will be discarded. In this publication we have a case study that proposes to solve these open points for applications that use the Perl language.

Background

Today, software engineers who propose to do their work using the Perl language and are concerned about the security of their codes, quickly encounter a problem: the absence of security technologies that support modern software development processes.

The quantity of options are extremely low, mostly commercial. Therefore, it is difficult to contribute to the improvement of its efficiency.

This same topic is also discussed in the publication: “Scaling Libs security analysis with Differential Fuzzing” [1], where a dynamic analysis solution is presented to identify vulnerabilities in modules/libraries.

Objective

In order to make the expected success tangible when using a tool focused on static analysis, the expectation is created that such an artifact meets at least the following requirements: In order to make the expected success tangible when using a tool focused on static analysis, the expectation is created that such an artifact meets at least the following requirements:

- Be fast to execute: in case of delay, this can be considered a friction for the development cycle;

- The user must be able to write his own rules: this is how we place them as co-creators of the technology;

- Low false-positive rate: we have limited resources so it is necessary to invest them where it really makes sense;

In addition to the basic requirements of the solution, such as: being able to say which source code will be analyzed, paths that the solution should ignore, which rules to use, among others.

Thus, this text will illustrate how a SAST tool for Perl applications can behave, what is its internal engineering. From there, its key results and limitations will be described.

Static Analysis

When we think about a simple and basic static analysis tool, focused on security, the general algorithm is something similar to:

- The SAST tool will receive a list of files to analyze;

- From that list of files, it will read the content line by line;

- Each line will be compared against a set of patterns (rules that have a pre-mapping of possible vulnerabilities);

- If any of these patterns exist in the line, the tool marks the line as potential vulnerable.

And in fact, there are numerous SAST tools that have a behavior identical to the one described. The problem with this approach is the fact that it doesn’t take into account the code structure or context, there are several gaps and this results in a bad experience due to little flexibility and a high rate of false positives.

The first point is that the first SAST tools (which some vendors still use this technology), made these comparisons listed in points 2 and 3 in a really direct way, a string comparison in the code file with another string in the rule, the famous “grep”.

This generates an extremely high false positive rate as we can point out a vulnerability that will be false positive:

- Based on a comment that exists in the code;

- A string constant that is printed and has the same name as a dangerous function;

- Several files that are not necessarily interpreted/compiled are analyzed, such as MarkDown and SVG, spending more time and resources;

Other than these points, rules usually only describe the use of dangerous functions, which do not necessarily reflect a vulnerability. For it to be considered a vulnerability, it needs to be exploitable, that is, an agent needs to have a control point to be able to act arbitrarily.

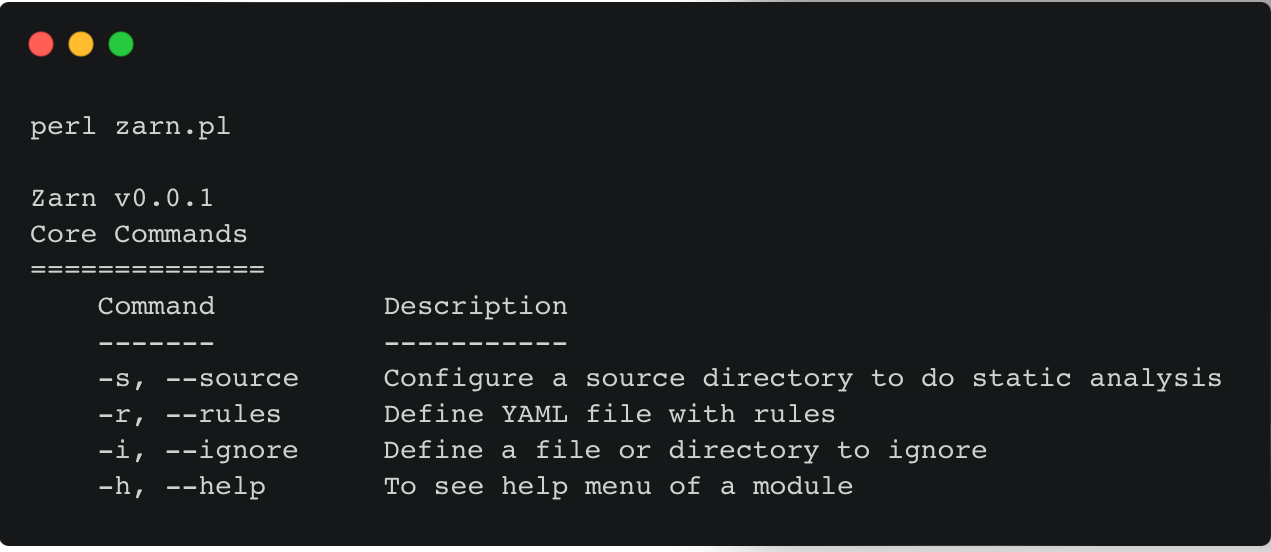

Introduction to ZARN

ZARN [12], a lightweight static security analysis tool for modern Perl Apps, seeks to resolve these points by adopting the following strategies:

To work around all these mentioned points, we have some extremely efficient approaches and the first one is that we only need to analyze the files that will be interpreted. In the Perl language, these will normally be files with the following extensions: .pl, .pm, .t. Also, if we know of files that will always be ignored, like for example the entire .git directory, we can set this as a default in order to optimize resources.

Example of this implementation: /zarn/lib/Zarn/Files.pm.

With this we will already notice a performance gain and also the number of false positives will be reduced, but it is still not enough. We also need a smarter implementation to parse the code, we can’t treat it like regular text.

Therefore, we can adopt the use of Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) [11], for our solution to parse only the tokens that relate to what we are looking for with the rules, without the need to parse strings or anything else when it doesn’t make sense. Here we make use of the PPI package, reading all tokens, ignoring comments and “PODs” [12]. If for some reason you are interested in understanding a little more about how the Perl Interpreter works, a good reading recommendation is: “Perlinterp - An overview of the Perl interpreter” [2].

Using AST (zarn/lib/Zarn/AST.pm) we ensure that only dangerous functions are identified and we enable the use of context, further reducing the false positive rate and improving performance.

The last point that needs to be worked out is to identify whether or not such a function is achieved by user input. This process is basically divided into the identification of “sources” and “sinks” and the correlation between them. [3].

In this way, when a dangerous function is identified, it is necessary to continue the analysis of the tokens in order to identify if there is a variable within that context, if it does not exist, we can discard the possibility of being a vulnerability, but if so, it is still necessary to identify whether this variable can be manipulated by the user or not.

For this last stage of variable manipulation identification, we adopted the Taint Tracking technique [10].

Basic Demo

An example in which we can understand in a practical way everything that has been presented so far would be the attempt to write a rule to try to identify a Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability in a simple piece of code.

There are numerous ways for code to be considered vulnerable to RCE, but here we will focus on trying to identify cases where the following functions are used in a user-exploitable way: system, eval, and exec.

Following the syntax used in ZARN, our rule would look like this:

rules:

- id: '0001’

category: vuln

name: Code Injection

message: “N/A”

sample:

- system

- eval

- exec

If Zarn is asked to use such a rule to parse the following code snippet:

#!/usr/bin/perl

use 5.018;

use strict;

use warnings;

sub main {

my $name = "Zarn";

system ("echo Hello World! $name");

}

exit main();

Zero vulnerabilities will be reported, although we have a system function, which has an external value being inserted, this value is not manipulated by the user. But if the $name variable is changeable by the user, it will flag the vulnerability:

#!/usr/bin/perl

use 5.018;

use strict;

use warnings;

sub main {

my $name = $ARGV[0];

system ("echo Hello World! $name");

}

exit main();

Result:

Future Work

Currently, Zarn do single file context analysis, which means that it is not able to identify vulnerabilities that are not directly related to the file being analyzed. But in the future, exist a plan to implement a call graph analysis [6] to identify vulnerabilities that are not directly related to the file being analyzed.

It’s already possible to use it in CI/CD pipelines, but the result is displayed as execution output. A possible improvement is to have the result being inserted into code repositories as annotations, improving the experience for users.

Conclusion

In order to collect clear evidence of the efficiency of the solution proposed here, ZARN was used as a strong support agent during the code review of 6 different projects.

During this review process, 11 findings were found using an initial set of 5 simple rules. 87% of these findings proved to be exploitable.

In the future, this same publication will be updated and will describe some of these cases with the aim of illustrating and facilitating the reader’s understanding.

References

- [1] https://heitorgouvea.me/2021/12/08/Differential-Fuzzing-Perl-Libs

- [2] https://docs.mojolicious.org/perlinterp

- [3] Sources and sinks

- [4] About Perl Tokens ignored by the interpreter

- [5] Taint Analysis

- [6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_graph

- [7] http://ods.com.ua/win/eng/program/Perl5Unleashed/ch11.phtml

- [8] https://www.cgisecurity.com/lib/sips.html

- [9] https://perldoc.perl.org/perlsec#Laundering-and-Detecting-Tainted-Data

- [10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taint_checking

- [11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abstract_syntax_tree

- [12] https://github.com/htrgouvea/zarn/

- [13] https://perldoc.perl.org/perlpod